Editor’s Note: This article is based on Dorota Shortell’s presentation at RoboBusiness 2025. Stay tuned for more post-show coverage and insights from this year’s event.

With the amount of attention given to robotics, humanoids, and physical AI, there are many new entrants and startups in the field. They often have great, even industry-changing ideas, but what will it take to turn a good idea into business success? We know that the majority of new businesses fail, so what did the ones that succeeded do to get there? Learning from both companies who have developed successful robotics businesses and also from those who have failed or had to pivot, gives newer robotics companies insights on what actions they should take to maximize their chances of building a sustainable business.

Tapping into both the 20+ years’ of hardware, mechatronic products, and automated robotic systems experience at Simplexity Product Development and interviews with leaders at over a dozen robotics companies, I’ve compiled these key lessons learned that I shared during my talk at RoboBusiness last week in Santa Clara, Calif. They can best be categorized as falling into 5 main categories:

- Product market fit

- Funding

- Development process

- Team

- Scaling

I’ll dive into each one in more detail, starting with a quote to set the stage.

1. Product market fit

“Understand the most important customer problems first and build new technology second. Building a new robot should only come after you have conviction that it will solve a problem worth solving. Otherwise, you risk building something interesting, but ultimately useless.”

– Christopher Carlson, executive vice president, research, corporate Development, and Intuitive Ventures

Carlson and I went to graduate school together at Stanford and over the past 12+ years he’s had a very successful career at surgical robot maker Intuitive. Intuitive has been a robotics leader for 30 years, so learning what they did in the early years and how they develop robots now is something that aspiring robotics companies could try to emulate. Christopher really emphasized how product market fit is one of the key distinguishing factors between success and failure, also echoed by quite a few of the other robotics leaders who I interviewed. The lessons under this category are:

Build your company around what people will buy: If you only take away one learning, it’s to be laser focused on developing a solution for a critical customer need versus focusing on building a robot. The companies who had to do a hard pivot or didn’t make it in the market most often cited that they were too focused on building cool robot technology and not spending enough time understanding customer needs. The advice here is to build your company around understanding your client, not just on interesting technological advances. A simple solution that solves a critical need is much better than a sophisticated solution that is only a “nice to have” for potential clients.

Use a fast feedback cycle – ideate, validate with customer feedback, iterate on the design: Once you understand what the critical need is that your company will be addressing, then it’s time to gather ideas for how to solve it and get as much feedback from customers as you can prior to building hardware. This will be limited as most customers will need to see/try what you are offering, but doing initial interviews helps narrow down the problem and define a product architecture that is more likely to be successful.

Dusty Robotics did this by interviewing clients for several months prior to building their robot. Then you need to build hardware, gather more feedback from customers, and keep iterating on the design, in fast cycles. Don’t be in stealth mode. Build in public since you don’t have multiple shots on goal. You have to know there is a market for what you are building when you go out there.

Secure a beachhead client and co-develop with them: Companies who were successful at focusing on the client said that co-development and having close collaboration was critical. Rather than trying to sell a completed robot into a client site, they would have their engineers at the client sites working alongside the client to hone the technology. This was most often accomplished by having a service business model rather than a product model.

For example, Dusty Robotics offered its robot as a service first, where they would print the construction lines on the new construction prior to trying to sell the robot. This allowed them to discover unstated customer needs such as that the weight of the robot needed to be light enough for a person to carry from floor to floor and to figure out how to account for winds present in open construction. They also didn’t need the robot to be perfect as they would bring another robot to the customer site as a spare in case the first one had any issues.

Don’t underestimate the challenges of technology adoption: While you hear that there may be resistance to clients adopting new technology, be careful not to be so enamored with your idea that you brush that aside. BioMotum realized this later in their development cycle. While they knew that an early design with cables was difficult for people to understand and put on, they thought that the fact that people would get such superior outcomes from using their robotic ankle assist device that how it looked was not as important. Only later did they realize that the user experience is critical to success of the company since if people don’t know how or aren’t willing to put it on, then the outcomes don’t matter. BioMotum’s CEO and co-founder, Ray Browning, stated “it’s never about the technology – it’s about using it.”

Simplify to only critical product features: It’s a big mistake to try to get every possible feature into the first release of your product. Rather, you need to be laser focused on the simplest incarnation of your product that people will buy. A process that Camino Robotics, a developer of robotic assist walkers for the elderly, used is to write down all the possible product features and then to have potential users choose which one of just two features at a time they would choose. They also had users walk through their day, which often revealed unmet needs. That helped narrow down the list to those features that were critical versus nice-to-have.

Also, another company, Civ Robotics, which is designing surveying robots for outdoor terrain, recommended having a cost associated with doing a pilot with a customer rather than doing it for free. People are most serious when money is involved. Make sure the problem you are solving is important enough to the customer, even if it’s technologically straightforward. Try to get revenue as fast as possible.

2. Funding

“It’s tough to work with the entrepreneur that knows everything. Easy to invest if they have an open mindset and know where they could use help”

– David Chessler, Chessler Holdings

Chessler is a successful investor, still in about 22 operating companies. He’s invested tens of millions in capital over the years and is currently running a program called HUSTLE on entrepreneurship in University of South Florida, which incubates student ideas.

It always costs more and takes longer than you think: A common reason companies fail is that they run out of money or cannot secure their next round of funding prior to running out of cash. New entrepreneurs are often surprised by how much additional costs the business ends up having beyond what was modeled in their first business plan. After all, you’re inventing something new and disruptive that the market hasn’t seen before, so you can’t have a perfect prediction of how much it will cost. What you can have though is estimates based on previous similar projects which mentors and companies who have previously brought products to market can help estimate. Listen and learn and add contingencies to your budget for the unknown areas that could take longer than you think. It’s also easier to raise more money if you have chosen your investors wisely and they are willing to keep investing in you for future rounds.

Develop a sustainable business model: Will you make money by selling your product or selling a service that your product can do? How many do you need to sell to breakeven? What are the ongoing costs once you do start selling them (warranty, continued development, fulfillment, inventory, etc)? How much cash will you need for up-front inventory costs? How will tariffs and supply chain disruptions affect your costs and timelines? What terms will you offer your clients? How will competitors react to your offering? What pricing pressures will you see? What are clients actually going to pay versus what they say they could pay? These are just some of the questions you should be answering. What founders also sometimes don’t realize is that the business model will likely reshape the architecture of your product. So getting that capability inside your company early on is critical to building the product or service offering that will allow your company to flourish for years.

Choose investors wisely: It’s tempting to take the first term sheet that is offered to you but remember that you are interviewing for a long-term relationship. One of the robotics startups that I interviewed commented that it would have been much more helpful if their investors had automation, hardware, and manufacturing expertise. It was always a challenge to explain those parts of the business and they didn’t have meaningful connections to leverage to help the entrepreneur in their business.

An investor that I talked with also mirrored that sentiment from the other perspective. If he doesn’t have the ability to stack the deck in his and the entrepreneur’s favor by introducing them to key clients or big players in the market, then he doesn’t feel his money will create a big enough impact to invest. Your major investors will likely also have a seat on your board of directors so make sure they can make introductions for you in your field and, in turn, make sure to be transparent with them on your progress.

What investors look for:

- Is it disruptive?

- What is the market size of the opportunity?

- Can we (the investors) add value?

- Is the team there to execute?

- How long will it take to get to implementation?

Try creative marketing to conserve cash: Once you receive funding, you want to stretch it as far as possible. There are two great examples of this that emerged from the interviews. The first is from Clayton Wood, former CEO of Picnic Works, where rather than getting a booth at CES, which costs tens of thousands of dollars, they got a spot in the area where food was served to demonstrate their pizza making robot. They ended up on three “best of CES” lists in January 2020 without incurring the normal expense that would take.

Another example is from Aadeel Akhtar, CEO and founder at PSYONIC, who has invented and developed an advanced bionic arm. Rather than paying for tradeshow booths, he walks around shows holding a live demo of his arm. He also gets in touch with YouTube influencers to feature the arm doing creative tasks like bottle tricks and flaming board breaking. Each of those videos ended up getting 2 to 4 million views, essentially for free.

Paint the future rather than explaining your product: One of the serial entrepreneurs whom I interviewed has been quite successful at raising money at multiple startups that he’s led over the years. I asked him what his secret is to being able to raise money repeatedly. He said that it’s all about storytelling, not explaining the product that you have. You’re not selling the product you have nor where you’re at. You’re selling what your product can enable in the future. How will your robot help address profound labor shortages or bring better tools that are simple to use that will extend the capacity of the labor? Paint a picture that your investors can see and feel.

3. Development process

“Early on it’s hard to get meaningful customer feedback about your idea without building it. Make something quick & dirty to learn from the customer as early as possible. However, if you build something too prototype-y at a later stage, the customer may reject it.”

– Philipp Herget, co-founder, Dusty Robotics

Dusty Robotics’ autonomous mobile robot prints construction drawings directly on the floors of new buildings. Dusty Robotics has been around since 2018 and raised over $69 million in funding.

Use off-the-shelf hardware and open-source software for your MVP: The robotics companies who have been successful found clever and quick ways of creating prototypes to show potential clients quickly. They cited using off-the-shelf development kits, open-source software, and portions of products already on the market to get a prototype that works well enough to start gathering real-world data and customer feedback. Only invent what you need. Civ Robotics is a good example of this who was able to start testing early versions of their land surveying robot within 4 months.

Embrace requirements, Gantt charts, and product process rigor at the right stage: There was a definite correlation between those companies who had formally written down their requirements and then followed a structured product development process and their success. The companies who struggled the most did the design in an ad-hoc manner. While this can be acceptable at first when you’re in experimentation mode (Phase 0 Exploration in the process chart below), it was inefficient and detrimental to success during the core development phases. Developing hardware is different than software. One of the comments I heard was that they should have gone slow to go fast. Slowing down, writing down requirements, planning, and following a proven development process for hardware saves time in the long run since you don’t end up redoing as much work. Below is an example of the product development process we use at Simplexity.

Create testbeds to test key functionality in parallel: One of the other mistakes that less experienced companies make when developing hardware is to build the entire product all at once and then test it. Subsystem testbeds let you test and iterate on the challenging subsystems without the distraction of interactions with other subsystems which may have their own issues. The more experienced companies interviewed build testbeds to dial in performance of a subsystem. For example, you can take the motor assembly mounted on a bench and test the end effector independently, allowing the engineering team working on the super structure to run in parallel. Don’t try to do the key science/invention simultaneously while trying to develop the product. Identify key risky core technology items first and de-risk them on well controlled testbeds.

Use digital twins and simulations: Digital twins or simulation can significantly speed up your development cycles. For example, you can simulate the dynamics of motion in seconds in a simulation versus doing it in hardware which can take days. But final testing and debugging are always done on the hardware.

Don’t start the FDA process too soon for regulated products: A few of the companies I interviewed had robotics products that were also medical in nature and regulated by the FDA. One caution they had was not to start the FDA process too early. Once you show your design to the FDA, then there is resistance in changing it, which may not be best for the product. When developing a product, you have 3 unknowns:

- Desirability: does your product satisfy an unmet need in the market?

- Feasibility: can you technically achieve the unmet need?

- Viability: is your business model viable enough to be competitive in the market?

To read more about these unknowns, check out Christopher Carlson’s article on a Sustainable Product Framework.

In the early stage, you want to bounce between assumptions on those three really fast. Only once you have proven that it’s a good idea, then you move to a more standard phase gate process that goes into the regulatory framework. Companies who had FDA regulated products cited how difficult it was to make the pivot to the product that would be needed to be successful in the market since they already had clinical trial data with their preliminary design.

4. Team

“Teamwork and leadership are complex character traits that are often referenced by many people but are widely ill defined despite the mountain of books and available classes.”

– George Linscott, formerly of Visicon Technologies

Linscott turned a commodity business into a highly successful product line. He grew the company into a profitable entity with over 100 employees and then had a very successful exit.

Founders, stay humble: As cited in the Investor section above, it’s acceptable, and even preferred, to admit that you don’t know everything as a founder. It’s much easier to invest in founders who have an open mindset and know where they can use help. Of course, you need to be confident and excited about your idea, but not to the point of having a big ego. Startups who have technically capable leaders who are also humble and value their team are the most successful.

Seek a strong technical co-founder with hardware development experience: One of the companies who shut down stated that they were missing a strong technical co-founder with hardware development experience. Having the right leadership internally, who understands how to develop products was a key differentiator. You need someone on your team who understands the nuances between different time constants of developing mechanical and electrical hardware versus software and how to optimize the interplay between them. It should also be noted that companies have been successful in outsourcing their engineering development to product development firms like Simplexity and even independent contractors, but having someone internally who helps drive the architecture and vision for the product is very helpful.

Hire the right people: When asking companies about their failure areas, a common trend noted was the difficulty of hiring and sometimes hiring the wrong person. This was usually due to hiring too fast, but even with the best interview process, with enough growth, a few bad hires can sneak in. Red flags to look out for are people with huge egos, who are toxic, and who are not coachable. You want to hire people with a growth mindset who are willing to learn. That said, you also want to hire the most experienced people that you can afford. Even though new college graduates are super smart and cost less in salary, the mistakes they can make due to lack of experience can cost the companies more than if they had just hired a more senior person. One person also noted to hire people who are “stubborn ” enough to fully finish a product. Follow-through and tenacity are critical in a challenging environment like a startup.

Develop your leadership & management skills: Being a founder and a good manager are two different skill sets. You can be a great technologist, but not necessarily a great CEO. While it’s certainly possible for one individual to do both effectively, leadership and management improve with training, coaching, and practice. If your company is successful, then your team will grow and you need to figure out how to develop and encourage them in a constructive fashion (or hire someone who can). These soft skills can sometimes be dismissed by gifted technical founders, yet the leaders who have decades of experience commented that those skills are what allow a company to flourish and continue hiring excellent employees.

Seek multiple mentors: You’d be surprised by how many people are willing to give freely of their time to help. Most people who are successful also want to see others have success and are willing to provide advice and mentorship when asked. It was also noted by one of the entrepreneurs that they benefited from different mentors for different stages of their company. Your company and your journey will keep evolving, so keep seeking mentors who continue to challenge your way of thinking and who are good at the next portion of your business. At first you may need someone who is good at getting funding, but then later you may need someone who has successfully scaled into high volume production.

5. Scaling

“Scaling is the hardest part, not engineering.”

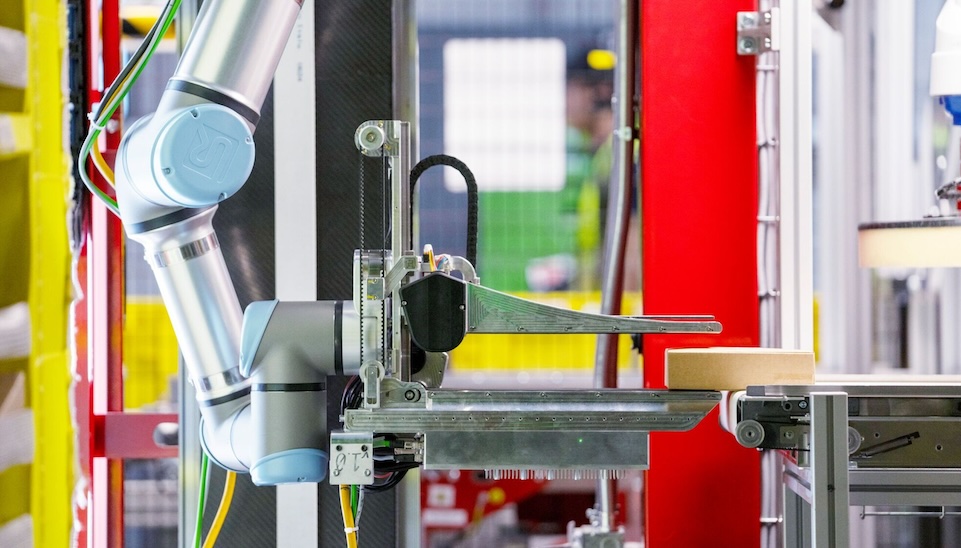

– Matt Frost, senior hardware manager, Amazon Robotics

Frost works on Amazon Robotics’ Vulcan bin picking robot. They’ve deployed Alpha systems and are now scaling up.

It’s easier to go from zero to prototype than from prototype to production: Even with initial success, businesses underestimate the effort it takes from building tens of units to hundreds/thousands. Design for manufacturing, assembly, service, test, and safety along with creating properly dimensioned GD&T production drawings, writing work instructions, qualifying manufacturing partners, and other New Product Introduction (NPI) activities take a lot of time and cost. One company said that the prototyping stage over 3 years cost less than 1 year of trying to get to production ramp. The design is not complete with the proof-of-concept prototype. That’s when the real work begins. Another one said that the cash hit for ramping up inventory was much higher than they expected. These are the types of costs that can sink a company and cause them to fail at scale, even after they have wonderfully functional prototypes and a good market fit.

Plan for & test your product: Planning for testing your product should be started at the beginning of your development as you write down the requirements. If it’s a true requirement, then there should be a way of testing it to confirm that the robot will meet it. This sometimes means putting in design features to make testing easier, such as test points on a custom PCBA design. Make sure you have a plan for how you will test individual subsystems and then your entire product coming off the manufacturing line early in the design process, not as an afterthought. Linscott stated that building testbeds in cooperation with their customers helped them avoid most major issues when doing acceptance testing. Another recommendation from a successful robotics company was to do highly accelerated life testing. Overload the system and over-cycle it to find the failure points early.

Automate for production: As you scale into higher volumes, you want to look for ways to automate or at least semi-automate the production of your robot. Semi-automated production may be a great fit for high quantity sub assemblies that require off-the-shelf pick and place, gluing or fastening technologies. Consider custom automation if necessary to manufacture your product and carefully analyze the cost benefit in all scaling phases.

Tariffs & multi-sourcing: In the recent political climate, several of the companies interviewed related that tariffs became unpredictable. They had to have a strategy for multi-sourcing their product manufacturing in different geographic regions. This is not simple to set up correctly, so working with a firm who can help you qualify contract manufacturers and have a design and manufacturing package ready to hand off to them for quoting is critical. If you need help, Simplexity does do this as part of our NPI process. A caution here is to be wary of contract manufacturers who are willing to do the design work for “free”. They do so with the stipulation that you will have them do all the manufacturing for your product and since you didn’t pay for the design, you don’t own it. It is then very difficult to move to another manufacturer or have multiple ones since then you need to pay someone to reverse engineer your product to get the design package you need to get multiple quotes.

Seek the flywheel effect: Once you have successfully scaled into volume, look for flywheel effects of creating a robotic system that can be applied to more than one customer need. For example, Intuitive was able to leverage the core mechatronic drive that they used for one application and then standardized it as a core capability for other adjacent applications. Their system that could reliably cut, sew, and retract created a flywheel effect once it was leveraged into applications beyond laparoscopy. This success allowed them to attract great technologists, retain them, and then make better products. Success breeds success.

Conclusion

I am grateful that over a dozen companies were willing to have a candid conversation with me about their failures and successes. While I had hypothesized that companies who showed their prototypes to potential clients sooner would be more successful, there was not a direct correlation. Even the companies who ultimately had to close their doors showed their technology early and got feedback. The key differentiator was the ones who were able to get revenue early from clients. Those who had customers willing to pay while still in development and co-develop with them were the ones with continued success. I encourage you to learn from all these lessons, be fanatical about understanding your customers’ pain points, build a strong team, and follow a proven process to help you achieve your goals. And if you need engineering help along the way, Simplexity is here for you.

About the Author

She is a US patent holder and has over 20 years of new product development experience. She was recognized by the Portland Business Journal as a Forty under 40 Award winner and an Executive to Watch.